Science Struggles with Communication

Science Struggles with Communication

Why is it so hard to understand modern science?

There's a great article in The-Scientist.com that talks about the history and struggles with bacterial cultivation and studies. It highlights perfectly that science is a cumulative process: modern science continues to grow from the mistakes and successes of the past. From a biological perspective, we still know very little about the organisms around us - there are hundreds of thousands of insects yet to be described by science and untold billions of bacteria.

The lack of complete understanding can make communicating science, scientific discoveries, and cross-disciplinary projects extremely challenging. Scientific journals do not allow discoveries to be published without providing 'convincing evidence' - which is then reviewed by a panel of 2-4 experts in a specific field of study (e.g. Biochemistry, Bryology). This process has its flaws but at its core it strives to provide a quality body of scientific works that the future 'modern science' can build upon. One major flaw with this is the cost to access these articles; if you're not affiliated with a university or college (whose budgets include millions of dollars to subscribe to scientific journals), it's not easy to find and read scientific works (or "primary scientific literature").

If journals aren't accessible, why don't scientists talk directly to the public?

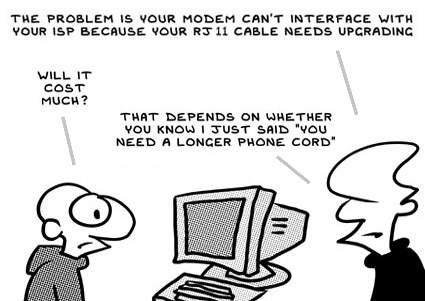

Part of the struggle to get scientists to report their findings to non-scientists lies in culture - the scientific culture loves specialized language. They live for jargon. When stripped from jargon, science loses so much precision, that some scientists don't believe it's worth talking about!

Part of the problem is that science, nature, and organisms are extremely complicated. To understand one tiny facet, you have to delve very far down the rabbit hole and it's really hard to dig back out.

Part of the problem is that science, nature, and organisms are extremely complicated. To understand one tiny facet, you have to delve very far down the rabbit hole and it's really hard to dig back out.

The Media is for Profit, Not Information

Most recently, scientists who do interface with the public directly have had a lot of negative experiences. There have been a lot of odd media frenzies lately (anti-vaccination, anti-GMOs, anti-climate change, etc) that circle around science and a lack of scientific understanding.

A scientist who wants to 'disagree' with popular beliefs is welcome to submit proposals and do experiments and try to challenge the norms - there's no conspiracy about this. Science is constantly challenging long-held beliefs!

Someone who claims to have evidence, but cannot provide any is easily dismissed by the scientific community. None of 'us' care unless you can show some well thought out experiments and data with robust statistics. Unfortunately, the media hasn't been as hard to convince and the public ends up hearing more fake-science from those speaking the most: the fake-scientist media hogs have the microphone.

"No legacy is so rich as honesty" - William Shakespeare

Many scientists don't love public speaking

Since we're speaking truthfully, let's be clear, many scientists don't like public speaking. This isn't shocking since most people don't like public speaking, but it is problematic. Historians write books (and make funny videos on YouTube) which the public can access in the library. Composers write music and the public can access it by attending performances or subscribing to music services. Artists create art and the public can see it at museums, studios, or online stores. Other professions have methods by which non-specialists can easily access their masterful works. If you can't read the papers because of paywalls or you cannot understand them because of jargon AND scientists don't want to give talks to the public, we're running out of channels quickly.

How can the general public trust scientific discoveries if there's still so much left to know?

The hardest part of science communication with the public seems to be the 'oops we were wrong' part. Nutrition science and meteorology are notorious for being wrong. First chicken eggs are healthy, then chicken eggs have too much dietary cholesterol, then chicken eggs are okay again. This type of back and forth shakes confidence in scientific findings, but it's actually completely consistent. Chicken eggs have been a part of European diets for a long time and seemed to be filling and nutritious. Upon closer study, it was found that eggs contained a high quantity of cholesterol at a time when heart disease and dietary cholesterol seemed perfectly linked. With more studies and more information, it became evident that dietary cholesterol is only one tiny piece of the story with heart disease; eating small eggs or just egg whites is very healthy.

So this brings up important questions: When should scientists share their findings? When they're new? If the findings might help people live longer and better? When results have been proven time and time again (sometimes taking 50 years)? If more than one experiment agrees?

How do we improve communication between scientists and the public?

There's no perfect time to talk about scientific research - setting realistic expectations is very important. New discoveries may not stand the test of time: Autism is not linked to vaccinations - it never was. The only evidence ever shown was found to be dishonest. But sick children is a frightening topic and fear sells, so the media feeds the flames.

Science isn't perfect - it's run by humans. Mistakes are made, politics are involved, and money makes for a poor honesty motivator. Credibility is important, but more so is evidence.

Asking questions is the most powerful tool anyone has - the more you know how something works, the better you can tell the truth and be wisely skeptical.