Sequence, Sequence Everywhere but Not Enough to Think

The Age of Sequencing Organisms

It's been 25 years since the first international effort to sequence the human genome began. Dubbed "The Human Genome Project" it took millions of dollars, thousands of scientists, and almost 10 years (as well as an unprecedented, wacky merger between public and private efforts).

Along the way, the technology & techniques the team created allowed the sequencing trend to encompass all manner of creatures - bacteria, fruit flies (drosophila), and mice - giving scientists all over the world a powerful tool to help understand pathogens, evolution, food webs, cancer, etc.

So what's the big deal?

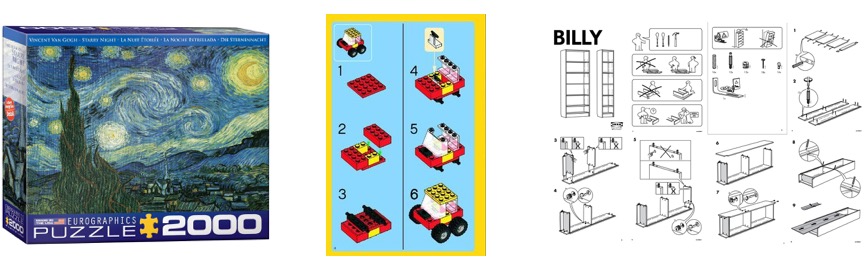

Have you ever put together a puzzle? A LEGO set? Perhaps a piece of IKEA furniture?

Imagine trying these projects without instructions.... Can it be done? Yes. Will you do it correctly the first time? Maybe; if it's not too difficult. Will you complete it correctly quickly? No. Absolutely not. In no way would that happen.

With a published genome, you have a box top; an instruction set; a better chance at seeing the big picture. Now, that instruction set is still published in another language... and sometimes pages are a bit creased or missing... but it's a start!

Sequence ALL OF THE THINGS!

Lots of other organisms are joining the club including plants (tomato, pumpkin, cottonwoods, cotton, pine trees), fungi, tiny, parasitic worms (nematodes), insects (honey bees, ants), and tons of other animals (platypus, snakes, dog, cat, horse) - there's even a project named "1000 genomes" trying to sequence and assemble more human genomes. Another project seeks to sequence 'anything' in the ocean they can scoop up!

Are We There Yet?!

So why don't we understand the entirety of the biological world??????

Well... image you took your LEGO instructions, and loosely used those steps to come up with a plan for your IKEA furniture... sure, you know the 'blocks' are different, but perhaps they go together the same way... Do you think your furniture would be built perfectly? That's what it's like assembling a new genome using an old genome as a scaffold. All of the flaws in the first one come over to the next. So all of the problems from the mouse genome show up in the human genome along with new problems unique to the human genome.. those then show up in dog plus new errors, which then effect cat..

Just because it fits and it seems to work doesn't mean it's the piece that belongs there.

Just because it fits and it seems to work doesn't mean it's the piece that belongs there.

Part of the magic of the "1000 genome project" is the goal of more "de novo assemblies" - throw away that first set of LEGO instructions and try to see how the IKEA furniture fits together - where do the pieces 'want' to go? Where do they 'fit' best? What process makes the most complete 'bookshelf' when it's all together (and what leaves the least number of 'extra pieces')?

What's the Moral Cinderella?

Knowing how to proceed, how to put all of the pieces together, and how to improve is never easy - be it about ourselves, our government, our environment, or our science. By working together and making genomes publicly accessible so that all scientists can use the data, we vastly improve the chances of moving forward.

In a world of genome editing, personal genome sequencing, and possible imminent mass extinction it's important to be curious as well as kind.